I've never posted twice in one month but this May recalls two events 20 years apart.

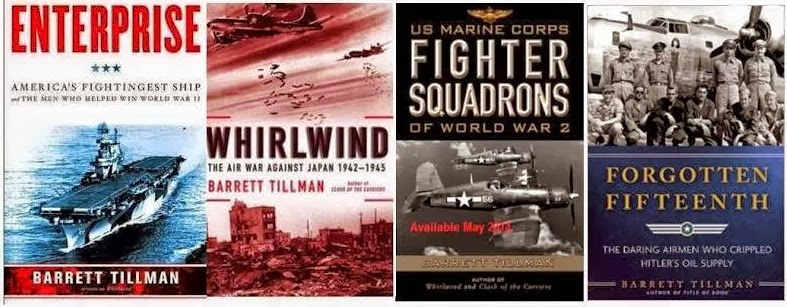

One of the most satisfying books I’ve written was Enterprise: America’s Fightingest Ship and

the Men Who Helped Win WW II (Simon

& Schuster, 2010) I knew so many Big

E men that I came to share their love for their ship, and on the 70th

anniversary of her last day in combat, I want to share events of May 14, 1945, well west of the International Date Line.

* * * * * * *

When the sun appeared over the

Philippine Sea at 5:30 a.m., the ship had been at general quarters for

ninety-three minutes. Hatches were

dogged; guns were manned; and battle rations available. The dawn revealed good flying weather: a

fifteen-knot southerly wind driving scattered cumulus clouds with bases at

3,000 feet.

Radar had

tracked twenty-six raiders inbound from Kyushu, and when the hostiles met the

task group’s Hellcat umbrella, some twenty-two Japanese succumbed to

interceptors or shipboard antiaircraft gunners.

One intended

to die gloriously.

Hellcats hunted a particularly cagey

Zeke playing three-dimensional cat and mouse. He ducked in and out of clouds, tracked by

radar and occasionally by optical gun directors, but the fighters could not

corner him. He was unusually persistent,

biding his time while making good use of the low clouds.

The intruder was Lieutenant (jg) Shunsuke Tomiyasu of the 721st Naval Air

Group. The 721st was deadly good at its

job. Ensign Kioyoshi Ogawa had expended

his life against the Bunker Hill three days before, forcing Vice Admiral

Marc Mitscher to shift his flag to The Big E.

Like

his squadronmate Ogawa, Tomiyasu was twenty-two years old. His relatives remembered him as a cheerful

young man, fond of sports and music, who dabbled in painting. He urged his family to “live with great

enthusiasm,” but Tomiyasu was equally capable of dying with great enthusiasm.

Now,

seeing an opportunity, at 6:53 Tomiyasu pointed his Mitsubishi’s nose at the

American carrier group and initiated a run, broad on the starboard beam.

The

sailors were alert. Almost immediately brown-black

splotches erupted beneath the puffy white clouds, radar-directed shells with

fuses containing miniature radio transmitters that detonated when they sensed

an aircraft nearby.

As

the Zeke sprinted from the clouds at 1,500 feet, Captain Hall ordered a hard

port turn. By swinging the stern to

starboard as the bow came left, Hall unmasked more antiaircraft guns and forced

the pilot to make a correction to avoid an overshoot.

Enterprise now got a good look at

Shunsuke Tomiyasu--his Zeke carried a large bomb. At 6:57 he came straight on, in a

thirty-degree dive, not jinking to avoid the flak and tracers that flashed and

flared around him. “Everybody unloaded

on him,” said Marine gunner Jack Maroney.

It

seemed incredible that an airplane could survive such gunfire. By one reckoning, the Zeke was subjected to fifty-five

barrels: 20 and 40 millimeter to five-inch.

Near the bottom of his dive, Tomiyasu recognized that he would overshoot to starboard. Two hundred yards out, in the final seconds

of life, he snap-rolled left to inverted and tugged the stick back, performing

the first quarter of a split-ess.

It was a beautiful piece of flying.

On escorting ships, men watched incredulously as the suicide pilot

performed an inverted forty-five degree dive into Big E’s fir flight deck,

splintering it just aft of the number one elevator. The hull trembled with the violence of the

ensuring explosion; men felt it throughout the ship.

The explosion lofted a large section of the fifteen-ton elevator some

400 feet into the air; the rest fell into the elevator well.

The bulkhead between the pilots’ staterooms was obliterated, leaving a

ballroom-sized pile of rubble. The

flight deck was bulged upward nearly five feet, and twenty-five aircraft

destroyed.

Lieutenant Commander John Munro already was one of the most experienced damage

control officers in the U.S. Navy. His ship

had been hit on March 18, March 20, and April 11—four times in seven

weeks. But the latest was the

worst—moreso than Eastern Solomons or Santa Cruz in 1942.

The information poured into DC Central: a serious fire in the forward

hangar bay, threatening ammunition lockers; the aviation fuel system was

ruined, lines severed and tanks leaking high-test gasoline. Seawater was streaming in unchecked through

breaches in the hull, and three- and six-inch water mains were broken,

aggravating the flooding. Any one of

those was serious; together they posed a catastrophic threat.

Yet Enterprise responded as

she had off Guadalcanal. The men, the

crew—the ship—fought back. Up forward

where the situation was worst, damage repair teams rushed to work. Hull technicians, carpenters, and bosun’s

mates gathered their gangs, shouted orders over roaring flames, and began

fighting the fight. Some sailors picked

up five-inch shells and powder bags, passing them hand to hand until the last

man in line pitched the explosives overboard.

Others sought the maimed, dead or dying and pulled, carried, or tugged

them out of the way.

Enterprise won her

fight in seventeen minutes. The worst of

the flames were suppressed and the rest finally extinguished in two hours.

Meanwhile, power to forward guns was interrupted or destroyed but other

batteries remained in the fight. While

the smoke still smoldered, Big E gunners splashed two more “bloodsuckers” in

the next hour.

That was the end of The Big E's long war.

Then it was time to count the cost.

Fourteen men were dead. About

sixty were wounded, half of them seriously.

The toll was small compared to the sixty-six crewmen Enterprise had lost at Eastern Solomons

and forty-four at Santa Cruz—let alone Franklin

and Bunker Hill’s hundreds. But shipmates are special in the sea

services, and three of the Big E’s dead sailors had been aboard since 1942.

One other casualty was tended to.

Tomiyasu’s body was recovered largely intact, and intelligence officers

retrieved his papers.

Much

has been made of the racial aspects of the Pacific War—perhaps too much. But generally the U.S. Navy accorded proper

if not Christian burial to dead Japanese: two instances involved the battleship

Missouri and escort carrier Sargent Bay. So it was in Enterprise. The medical

department sutured the enemy pilot’s wounds; his body was enshrouded in a

mattress cover, then committed to the ocean.

The

kamikaze’s name was improperly translated as “Tomi Zai,” and remained so for

decades. But assiduous research on both

sides of the Pacific finally solved the riddle, and some of Tomiyasu’s personal

effects with pieces of his airplane were delivered to his family in 2003.

* * * * * * *

In

2010 I received a letter from a Big E radar specialist. It contained a hand-written note appended to

an envelope: “Thought you’d like to have this.”

Inside

was a fairly crisp Japanese 50-sen note with the comment, “This was in

the pocket of Tomi Zai, 14 May 1945.”

I’m

keeping that irreplaceable bit of history in a safe, dark place, until I

determine what to do with it.